Transplantation

The idea of substituting missing or injured organs with healthy ones has always fascinated people. Many legends and myths tell of organ and fabric transference. The twins Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian are told to have succeeded in transplanting a dead man's leg in the third century A.C.

From Idea to Implementation

Bridging the gap between transplantation myths and medical procedure took many centuries. At times, the hurdle between idea and successful transplant seemed almost too high. The central challenge for medical scientists was, and still is, getting a handle on the recipient’s immune system. The immune system is designed to protect the body from invading substances and therefore makes short shrift of all foreign (exogenous) substances. Under regular conditions, we have reason to be grateful for the good work our immune system is doing for us. However, the immune system’s virtue turns into a bane after organ transplantation. Soon after transplantation, the immune system will declare the new organ a foreign invader and reject it.

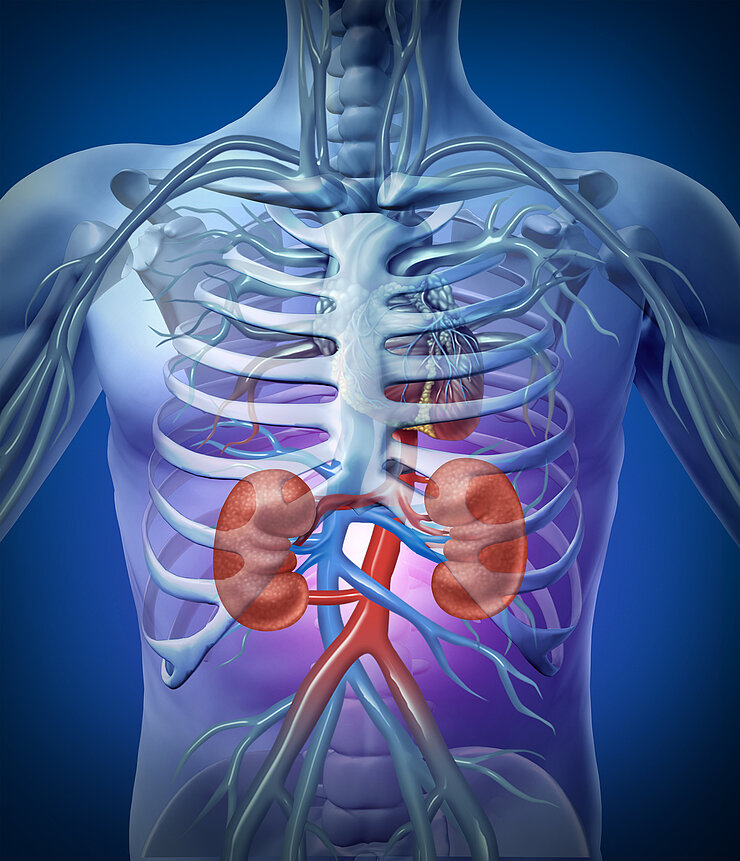

For a long time, close genetic similarities between organ donor and recipient seemed prerequisite to preventing organ rejection. Surgeon Joseph Murray and his team counted on matching genes and tissues when they planned and successfully performed the first organ transplantation in 1954. Joseph Murray transplanted a kidney from one identical twin to the other. This was the first of many successful organ transplantations. Today, transplanting kidneys, livers, and even hearts are regular medical procedures.

Immunosuppressants are the Key to Success

We asked the Deutsche Stiftung Organspende (DSO, German Foundation for Organ Donations) for data and learned that in Germany alone 1,550 kidneys and 846 livers were transplanted in 2015. Thanks to the development of immunosuppressants, close relatives are no longer the only potential organ donors for recipients. Immunosuppressant drugs dampen the immune system or reduce its efficacy enough to prevent the rejection of transplanted organs. The development of immunosuppressants began in the 1960s with the discovery of Azathioprine. This drug suppresses the proliferation of T-cells (one of several cell types in the immune system). T-cells are the first line of the immune defence against substances, which are alien to the body. They initiate the immune response.

Meanwhile, researchers discovered a catalogue of immunosuppressants. The drugs prevent the organ rejection by interfering with various steps in the immune response. Using combinations of immunosuppressants is a particularly promising approach. The required dosages vary from patient to patient and also depend on the transplanted organ.

Suppressing the immune system comes with a risk. The tuned down immune system is no longer as efficacious as before. Patients taking immunosuppressant drugs are especially susceptible to infectious diseases and require prophylactic treatments against these diseases.

Step by step, researchers improved the techniques and immunosuppressants. They accomplished much since the first successful organ transplantation. Once, humankind dreamed about organ transplantations. Today, organ transplantations are almost routine procedures. However, a different kind of problem surfaced, which medical research cannot solve: There are not enough organ donors. Fewer and fewer people are willing to donate organs.

(rwi)

Involved research groups

-

Viral Immunology

Prof Dr Dr Luka Cicin-Sain

Prof Dr Dr Luka Cicin-Sain