The most widely known Yersinia germ is Yersinia pestis, the cause of the plague that can be transmitted by fleabites. Other species, such as Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, usually enter the human body via contaminated foods, for example raw pork meat, and can elicit severe diarrhoeal diseases or vomiting. This is how the body eliminates the majority of the pathogens, while the immune system takes over the remaining clean-up work. However, a Yersinia infection can just as well become chronic and then even promote autoimmune diseases, such as reactive arthritis. But it is still unclear how the bacteria manage to survive for years inside the body without being detected by the immune system and how they promote immune reactions against a body's own tissue.

Some Yersinia strains produce a toxin called CNFY during the acute infection phase and release it into the host cells. Once inside the cells, the substance blocks cell division which, in turn, leads to a steadily increasing cell size and facilitates the attack by the pathogen. "Yersinia uses CNFY to accelerate the spread of the infection and inflammation in the tissue, which is ultimately fatal for the infected host," says Prof Petra Dersch, who is the director of the "Molecular Infection Biology" department at the HZI.

Mice usually overcome a Yersinia infection rapidly and without being harmed. Approximately ten percent of the cases are fatal and approximately ten percent turn chronic. Petra Dersch and her team of researchers at the HZI applied state-of-the-art sequencing methods to look very closely at the mice showing a chronic course of disease and the associated Yersinia germs: A transcriptome analysis revealed which genes in the bacteria and the mice are active and which are not. "We found the production of CNFY in the persisting, i.e. surviving, yersiniae to be down-regulated," says Dersch. "But in the absence of CNFY, the immune system no longer detects the bacteria, the inflammatory reaction subsides and the mice survive. This trick allows the yersiniae to hide for months in the caecum (appendix) of the mice."

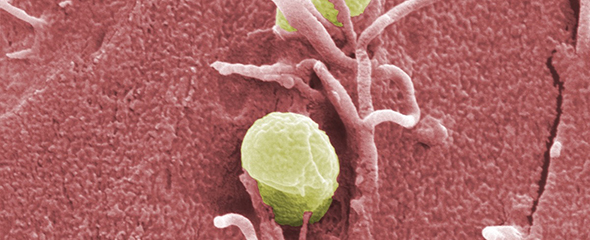

Tissue analyses done by microscope also reveal a difference between yersiniae causing acute versus chronic infection: During acute infection phases, the rapidly growing bacteria produce micro-colonies that are recognised by the immune system. In contrast, the persistent bacteria are found as single cells within the tissue, which makes them more difficult to detect. Collaborating with Dr Till Strowig, the head of the "Microbial Immune Regulation" Young Investigator group at the HZI, the scientists also showed that Yersinia pathogens can even change the microbial community in the intestines.

A Yersinia infection shifts the composition of the microbiota in the intestines in favour of inflammation-promoting bacterial species

It has been known for a long time that there is a correlation between Yersinia infections and inflammatory autoimmune diseases, such as a reactive arthritis, but the underlying mechanism is still unknown. "Our transcriptome analyses showed that the immune response to the residing bacteria in the chronically infected mice is rather inconspicuous, but still detectable," says Petra Dersch. "Consequently, antibodies against inherent tissue might be produced since some of the surface structures of the host cells resemble those of the bacteria. This might also explain the increased manifestation of arthritis in Yersinia patients."

In January, Petra Dersch was admitted to the European Academy of Microbiology. Founded in 2009, the Academy promotes microbiological research in Europe and aims to cross-link the scientists more closely. To this end, the Academy organises meetings and congresses and develops recommendations concerning critical issues of microbiology. The members of the Academy are renowned scientists who are elected by the Academy.

Original publication:

Wiebke Heine, Michael Beckstette, Ann Kathrin Heroven, Sophie Thiemann, Ulrike Heise, Aaron M. Nuss, Fabio Pisano, Till Strowig, Petra Dersch: Loss of CNFy toxin-1 induced inflammation drives Yersinia pseudotuberculosis into persistency. PLOS Pathogens, 2018, DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006858