The human body is colonized by a variety of different microorganisms such as bacteria, yeasts and fungi. All these microbial co-inhabitants - known as the microbiome or microbiota - are important for our health: For example, the microbiome in the gut supports digestion and helps to make nutrients available. Although certain groups of bacteria dominate the human gut microbiome, the exact composition varies from person to person. For example, bacteria from the Prevotellaceae family and the associated genus Segatella are very common, but not much is known about their biology as they are difficult to isolate and cultivate. They are part of the original microbiome and are found in around 90 percent of people living in non-industrialized regions around the world such as the Amazon or parts of Africa. In contrast, only 20 to 30 percent of people in Europe and the USA carry these bacteria.

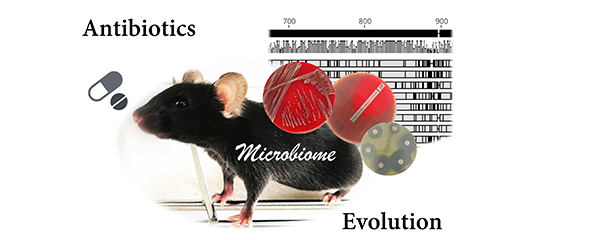

A research team led by Prof. Till Strowig, who heads the "Microbial Immune Regulation" department at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) in Braunschweig, recently succeeded in isolating additional representatives of the Segatella bacterial members. "With high-resolution and high-throughput genomic analyses, we were able to show that the Segatella group along with the well-known representative Segatella copri (previously known as Prevotella copri) is a much larger complex than it was previously known, with five species which were never described before," says Strowig. With joint efforts from the Leibniz Institute DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH and the University of Trento (Italy), the research team has comprehensively characterized these species regarding their genomic diversity, biological features, and links with human health. "Segatella are specialized in the degradation of dietary fibres. However, it is still not known whether or how they benefit our health," says Strowig. The fact that they occur much less frequently in the microbiome of people living in the westernized world is probably a result of the hygienic conditions: "Due to their extreme specialization in humans, these bacteria are mainly acquired through interpersonal contact, not through food, and intensive hygiene measures can break such natural colonization chains."