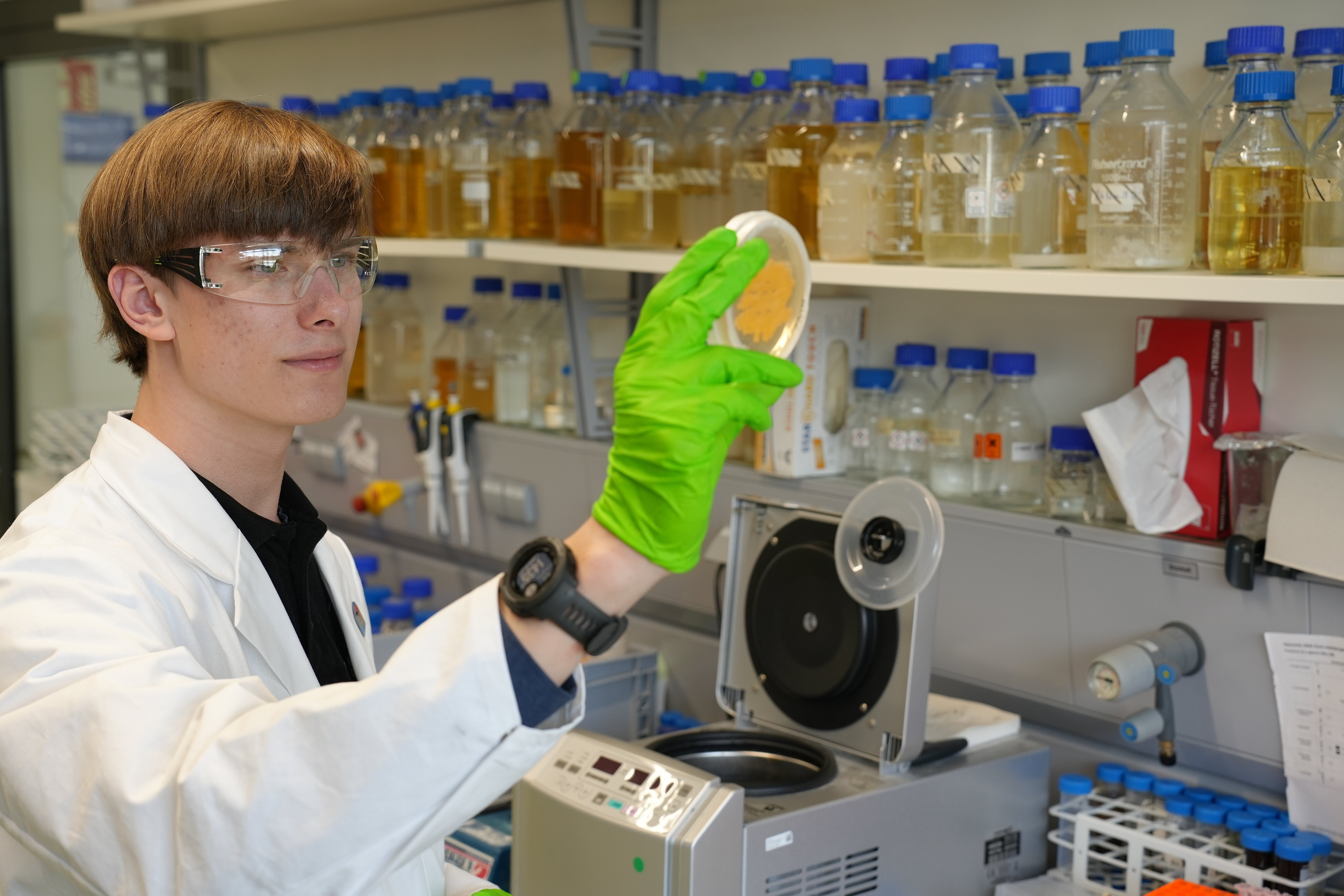

Alexander, you recently won the Saarland state competition Jugend forscht in the field of biology - congratulations! What was your project about?

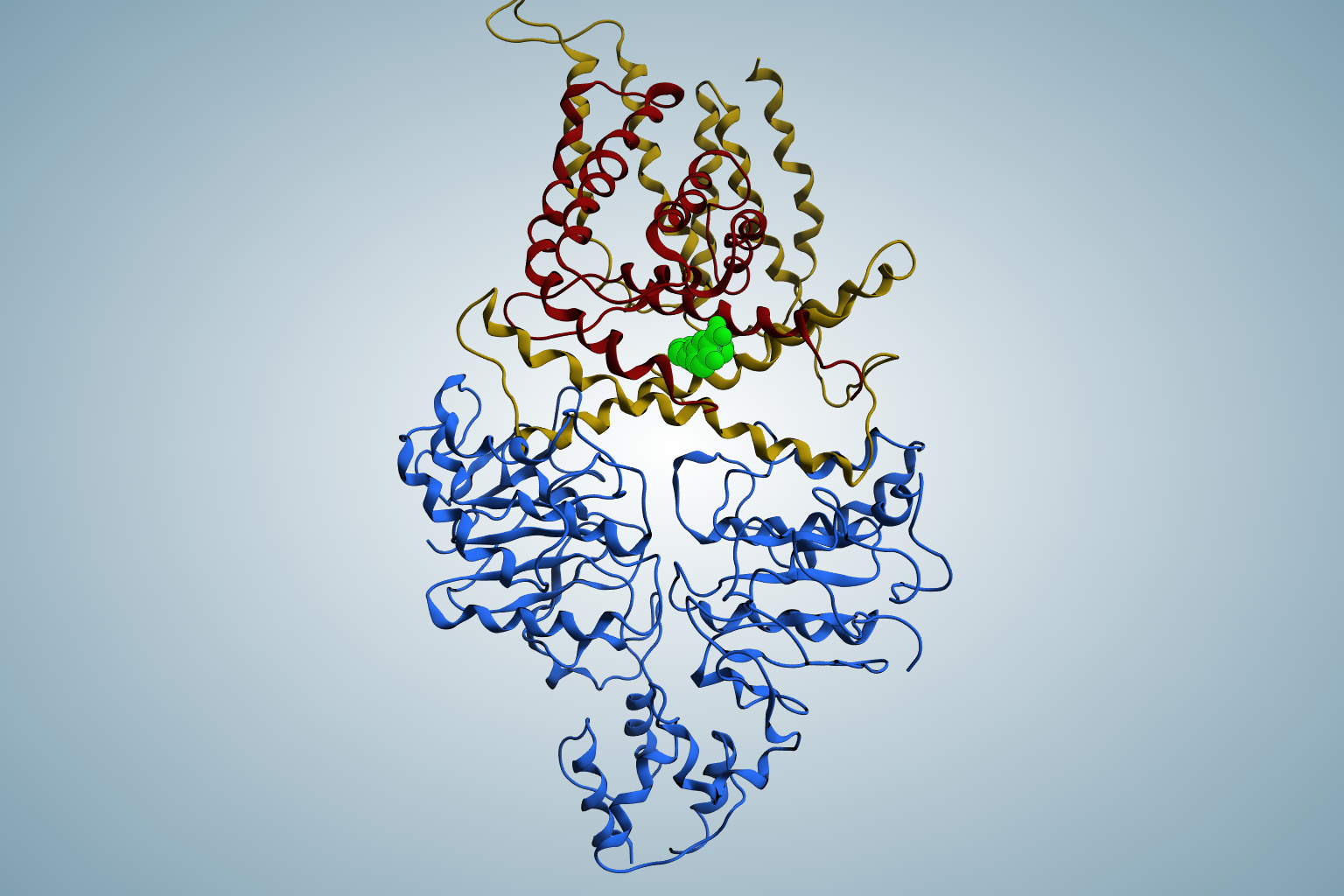

The project focuses on the search for interesting bacteria from copper mines that are capable of producing new useful substances, such as antibiotics. One of the most promising approaches against multidrug-resistant germs is to look for new active substances in microorganisms that are in competition with bacteria and therefore produce antimicrobial natural products. In my work, I have found so-called myxobacteria. This is an order of very exciting bacteria that hunt other bacteria in swarms. In order to digest their "prey", they produce a variety of antibiotically active substances that could potentially be used pharmaceutically in the future. I was supported in my project by HIPS scientist Daniel Krug, who also visited the copper mines with me.

Why did you choose to focus on copper mines? Aren't they rather hostile places?

That's right, copper and copper-containing compounds are known to be very harmful to most organisms. For this reason, copper-based coatings are already being investigated to combat germs, e.g. for door handles in hospitals. However, there are also bacteria that can tolerate more copper and still grow on such surfaces. Copper also plays an important role in immune defense. This means that if copper tolerance is switched off in some germs, they are no longer infectious. This makes such tolerance mechanisms interesting targets for new active substances. In addition, we expected to find rather unique and adapted microorganisms in such hostile environments. The work on the project has shown that many different bacteria, including previously unknown ones, can be found in copper mines. In one mine, we were even able to discover a giant fungus covering an entire corner of the tunnel.

How did you get into the mines? There hasn't been any copper mining in Saarland for a long time, right?

That actually took a lot of preparation. After some research, I was able to find three mine systems and made enquiries with those responsible. Initially, these were the visitor mines in Düppenweiler and Fischbach in Rhineland-Palatinate. The manager in Fischbach was very curious about the project and agreed to open up the visitor mine for us. Due to a misunderstanding, I didn't come into contact with the visitor mine in Düppenweiler, but with a research excavation right next door, which is investigating historical mining on the site. That was even more interesting. This tunnel is still relatively new and, as no visitors are allowed through, the microbial ecosystem is less disturbed by humans. The people in charge were skeptical as to whether we could find anything there, but allowed me to collect some samples anyway. The third mine was the most exciting. The Sonnenkupp gallery near Wallerfangen dates back to Roman times and was last closed in 1857. After many phone calls to the district of Saarlouis, I got in touch with the conservation officer and head of the Historical Mining Working Group at the Wallerfangen Historical Museum. He was also very interested in the project, opened up the mine to us and even gave us a detailed tour of the tunnel.

How far did you get in your search for new bacteria and natural products? Have you already made an exciting discovery?

I have been able to identify 85 new strains so far; currently I am working on another dozen. Among them are at least 18 new species and new genera or bacteria even more distantly related to known organisms. Interestingly, the same Myxococcus is found in different samples from two mines. It is possible that this strain is specifically adapted to copper-rich environments. I would definitely like to take a closer look at this. It is also capable of producing an already known antibiotic, called myxalamide. This raises hopes that this species is also capable of more. A few of the other bacteria are also already showing that they can produce some antibacterial compounds. However, more detailed investigations are still pending.