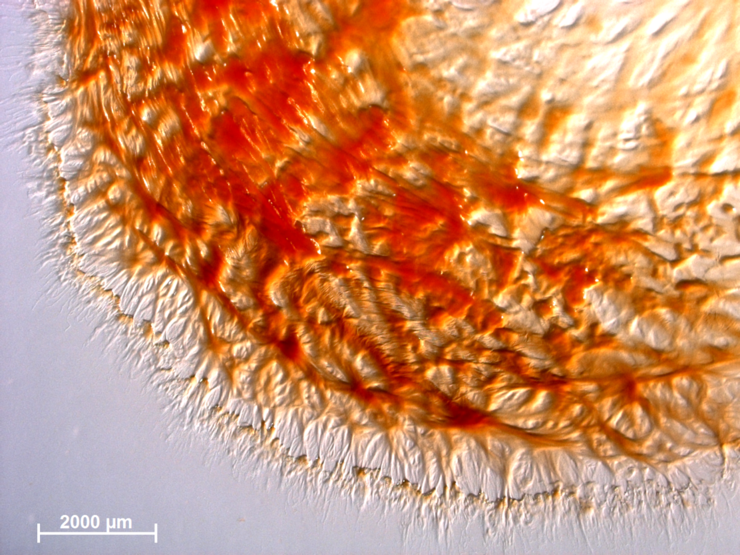

The increasing resistance of pathogens to known antibiotics is an alarming trend that has gained public awareness over the last couple of years, as more and more infections with multi-resistant germs are reported from the clinics where even treatment with reserve antibiotics fails. Scientists at HIPS – an institute jointly founded by HZI and Saarland University – are therefore investigating myxobacteria as a source of new anti-infective compounds. The soil-living myxobacteria, once regarded as exotic newcomers in natural products research, have in fact a long-standing tradition at HZI in Braunschweig where the scientists Hans Reichenbach and Gerhard Höfle worked for decades to establish a worldwide strain collection. Nowadays myxobacteria are well known as a valuable source of natural products, whereas many of these so-called secondary metabolites show intriguing chemical structures and often exhibit potent biological activity. The myxobacteria collection has grown to contain more than 11,000 strains to date, and modern genomics- and metabolomics-based methods are applied at the HIPS department “Microbial natural products”, which is led by Prof Rolf Müller, in order to uncover the chemical secrets from this microbial treasure chest. An exciting undertaking, as any novel chemical entity revealed raises hope that the new molecule could serve as the starting point for development towards a much-needed therapeutic agent.

“Sample das Saarland” – microbial treasures from soil

Visitors approaching the new HIPS building on the Saarland University campus will catch sight of a large poster: “Sample’ das Saarland – Mikrobielle Schätze aus dem Boden” highlights the main research objective, followed by a call to help the HIPS scientists with soil sample collection. Are today’s scientists tired of adventurous expeditions to retrieve soil samples from remote locations around the globe? Dr Ronald Garcia, microbiologist at HIPS, is eager to explain matters: “We do have agreements with a few countries for collecting soil samples. However, negotiating such contracts is always a lengthy process with uncertain outcome and generally comes with enormous judicial burden due to legal implications from the Nagoya protocol. In contrast, local sample collection is uncomplicated and we are confident that any ecological habitat accommodates a highly diverse microbial community.”

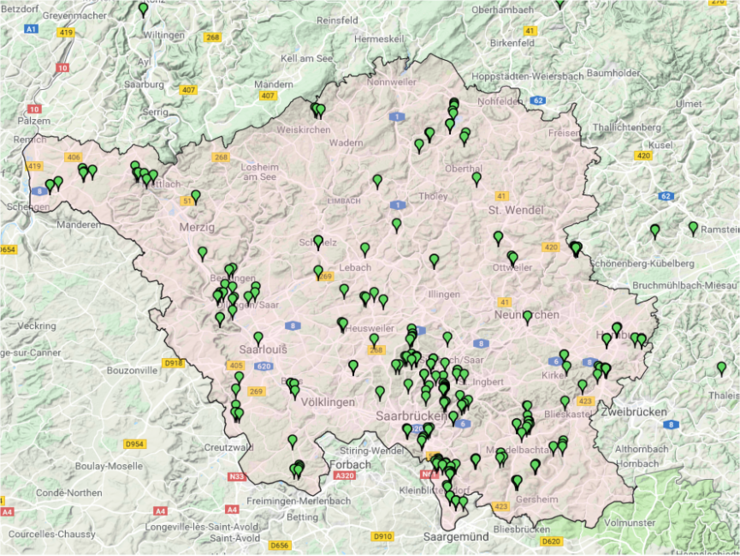

The idea of conducting a sample collection campaign in the Saarland region as a citizen science project originated from the planning of activities for a HIPS open day. Scientists then went on to manufacture sample collection kits (the most important part in these being a blue plastic spoon and a sterile barcoded plastic bag) and set up a website where collected samples can be registered on-the-spot. Sample kits also contain a leaflet with detailed instructions for sample-taking, a post-free reply envelope and a tiny magnifying glass. More than 600 of these sample kits have already been distributed, and they can be ordered via the website (http://hips.saarland/sample). A real-time map shows the current status of sample collection. When the first soil sample packages arrived by mail, the project initiators were happy: “At this point in time we realised that the concept could actually take off,” says Garcia. Compared to soil samples collected by the researchers themselves, the samples sent by citizen scientists do not stand back in any way. “The methods used for isolation of new bacteria are key to success,” says Garcia. “We employ a highly selective procedure to favour the isolation of new myxobacteria, and due to the natural products they make these are very effective in defending themselves against other bacteria. Our prospects for the discovery of new myxobacterial species are therefore not troubled by contamination with germs commonly found in soil.” The “Sample’ das Saarland” campaign is now already running for the second year, and scientists are pleased with the outcome. Participants are highly motivated and some even contribute their own ideas, sending the project team emails and even hand-written letters with suggestions about special locations, such as slag-heaps grown over with wood or abandoned mining areas barred for public access. Others are concerned about the isolation methods and propose to pretreat samples in certain ways in order to increase chances for finding uncommon bacteria.

Until now, Garcia and his colleagues were already able to characterise more than 200 new myxobacteria from Saarland soil samples, and some of these turned out to be members of previously unknown genera as judged based on their low degree of genetic relatedness to the known myxobacterial species. “If we obtain a few hundred additional strains, that will enable us to perform statistics-based analysis of myxobacterial secondary metabolomes in order to find new natural product candidates with the help of mass spectrometry,” says Chantal Bader, PhD student at HIPS. “However, there is more to it than just a high number of samples – we really need to make sure to include new and rare taxonomic groups of myxobacteria in our analysis. These come with an increased likelihood for the production of novel bioactive compounds having a previously unseen molecular structure.”

More and more citizens living outside the Saarland region ask the HIPS scientists if samples from other German regions would be of interest. The answer is clearly “Yes”, and indeed preparations are already underway to develop the citizen science project into a nationwide campaign. “The financial effort necessary to extend the campaign is favourably little, but we need to further develop our infrastructure. Right now, we are finalising a mobile app that improves the sample registration process including precise recording of geo coordinates,” says Garcia and adds as an outlook: “Who knows – maybe sending soil samples in the future will become just as common as blood donation.”

Author: Daniel Krug

Published: November 2018