Bacterial cells differ fundamentally in their structure from animal and human cells. For example, bacteria have a rigid cell wall, whereas human cells are surrounded only by a simple membrane. If a pharmaceutical agent targets cell wall construction, only bacterial cells are affected. This principle is an important basis for the development of antibiotics, since these should only act on the disease-causing bacteria, but not humans themselves. In their search for new active ingredients, a research team led by HIPS department head Prof. Anna Hirsch has now taken a closer look at a less obvious difference between bacteria and humans that has not yet been pharmaceutically exploited: the so-called methylerythritol phosphate pathway, or MEP pathway for short. The HIPS is a site of the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) in collaboration with Saarland University.

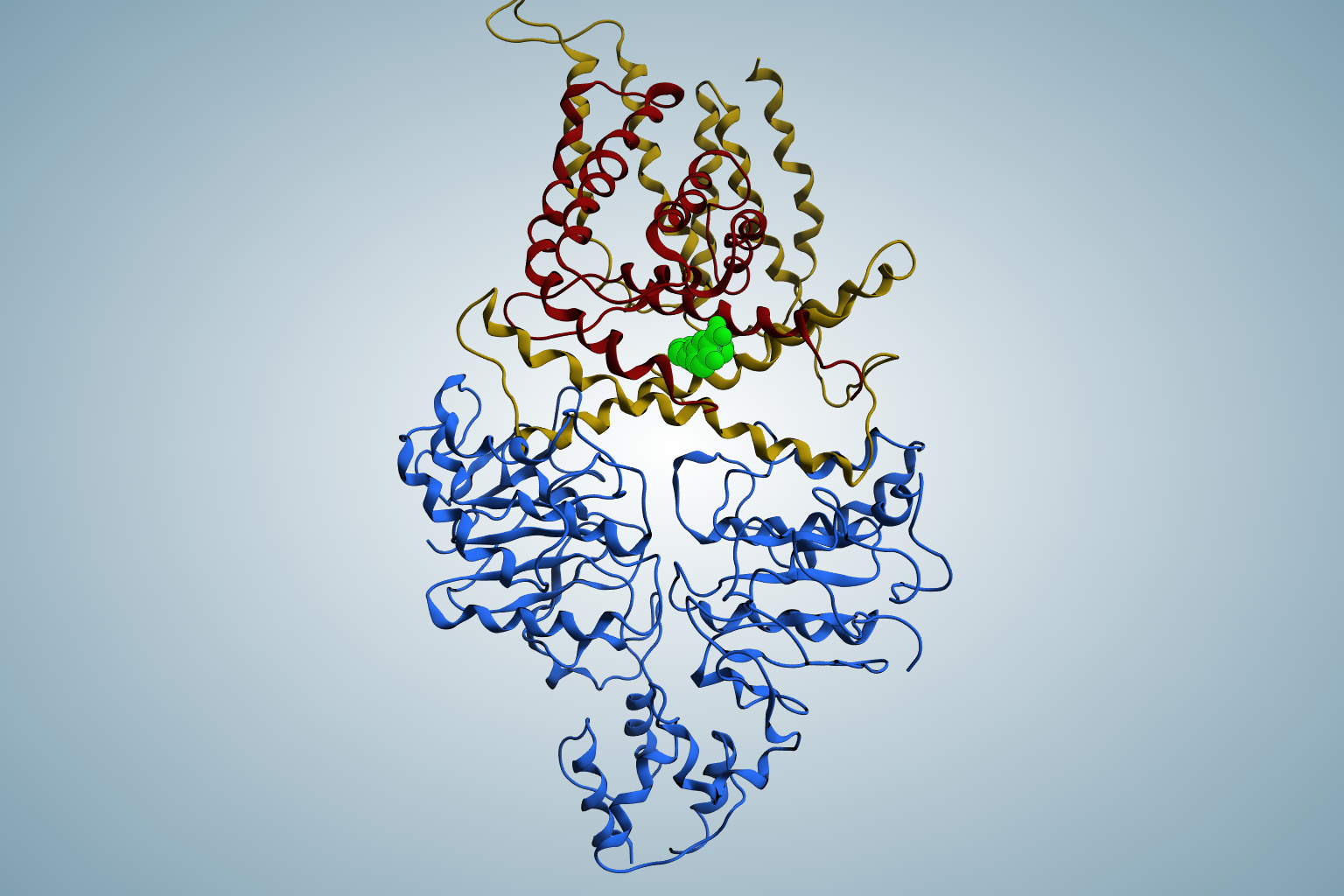

The MEP pathway is an essential part of the energy metabolism of several bacteria, including the hospital germ Pseudomonas aeruginosa. If the MEP pathway in bacteria is blocked, for example by a drug, they can no longer produce a number of vital natural products and subsequently die. Human cells do not have the MEP pathway and would therefore not be affected by a respective drug. In the search for such an active substance, Hirsch's team together with the group of Franck Borel (University of Grenoble) as part of a consortium funded by the European Union has analyzed the individual steps of the MEP in great detail. Their focus was on the enzyme IspD, which is responsible for the third step in the MEP Pathway. The researchers were able to solve the crystal structure of IspD from P. aeruginosa for the first time, thus gaining deep insights into its structural composition. With the help of the information obtained, the team was able to investigate how a specific chemical fragment binds to the enzyme. This so-called complex structure has enabled the design of optimized derivatives that make even better use of the binding pocket and thus bind more strongly to the enzyme.

“The fragments we synthesized bind excellently to their target protein IspD, and their other pharmaceutical properties also offer a promising basis for the development of new active ingredients,” says Eleonora Diamanti, project manager of the consortium and now assistant professor at University of Bologna. Hirsch, who also holds a professorship in medicinal chemistry at Saarland University, says: “What makes the newly developed molecules so special is that they target IspD, a protein that is not addressed by any drug currently on the market. This is the only way to ensure that a potential new antibiotic will also be effective against pathogens that have already become resistant to most conventional drugs.”

Hirsch and her team are currently working on the further development of the new molecules. To this end, they are planning to collaborate closely with the planned excellence cluster nextAID³, in which unexplored targets such as IspD will also play an important role. The next steps include efficacy studies in bacteria and the optimization of efficacy and other pharmaceutical parameters.