Early in the pandemic, there was a lack of masks and protective equipment for medical staff. Only insufficient capacities for contact tracing were available to the health authorities. There were bottlenecks in hospitals, lockdowns, school closures followed by the initial vaccine shortage - much did not go well. While the consequences and collateral damage need to be analysed, we also need to focus on precautions for the future. “The Corona pandemic showed us clearly, and often painfully, where things are stuck,“ says Prof Dirk Heinz, who is the Scientific Director of the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI). “All sectors of our society need to learn from this and get better organised: Developing emergency plans, guidelines, improved infrastructures. And research and development should continue to be supported strongly - to make sure that we are much better prepared for the next pandemic.”

“There will be other, perhaps even more dangerous pandemics”

Because one thing is certain: There will be another pandemic. We do not know when this will be or which pathogen to deal with at the time. “We need to keep a close focus on potentially hazardous candidates and monitor if and how these change in their behaviour,” says Heinz. “And we need to intensify our research on the pathways along which pathogens come to us. This includes particularity the conditions under which these zoonotic pathogens jump from animals to humans.” This is a key question to be investigated by the new Helmholtz Institute for One Health (HIOH) in Greifswald, which is another site of the HZI currently being set up.

Fast and targeted action

“It is also important that we take infection events in foreign countries more seriously in the future and react more quickly,” says Dr Berit Lange, head of Clinical Epidemiology at the HZI. “We used to think, mistakenly, that infectious diseases pose no real hazard to us in Germany or Europe. Regrettably, this is not the case. We need to be aware: There will be further, possibly even more dangerous pandemics in the future.” When a new pathogen emerges and another pandemic looms, speed is essential. “The wait-and-see approach will only result in more infections, more severe courses of disease and more deaths,” says Lange. “Of course, we must take the proper actions that are specifically aimed at the pathogen in question to protect the most vulnerable population groups.” This means: The more we know about the pathogen early on in the pandemic - i.e. about its transmission and the incubation time - the better and more specifically we can react.

For this to be successful where it is needed, key sectors of society need to have effective pandemic plans in place. “The Corona pandemic showed that the educational and labour sectors were not prepared properly,” says Lange. “Now is the time to make improvements, to develop pandemic plans and guidelines for businesses and schools to provide effective infection protection in the event of the next pandemic, to avoid lockdowns if at all possible and to better mitigate its impacts.”

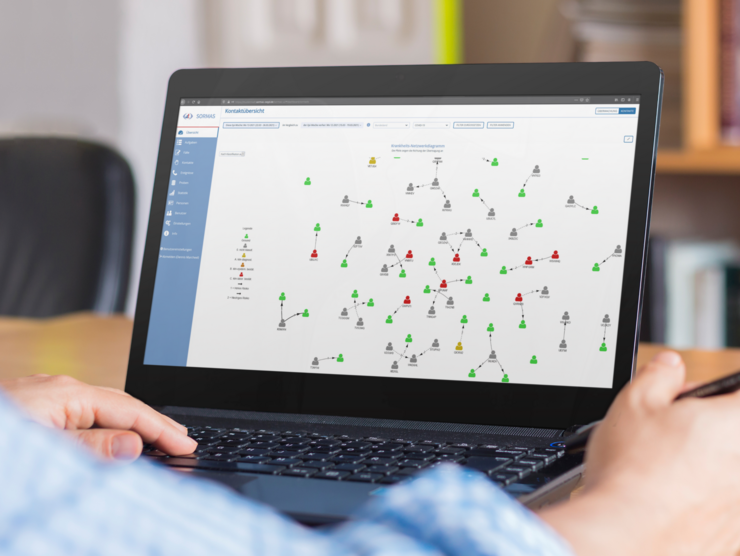

Where do most of the infections take place? How many other people does an infected person infect on average? Does the pathogen become more contagious, deadlier? “These are important epidemiological questions that can be answered through detailed contact tracing and timely analysis of the data,” says Lange. Especially contact tracing is one of the key instruments for containing a pandemic. “For the future, we urgently need to expand the administrative capacities and infrastructures in order to detect hotspots of infection early and to be able to contain them on a regional level through targeted actions.” During the Corona pandemic, the digital system SORMAS, developed by the HZI and partners, is helping to improve the management of contacts and infection chains as well as the digital exchange between the health authorities. SORMAS, developed in 2014 in the light of the large Ebola epidemic in West Africa, was adapted to SARS-CoV-2 in 2020.

Getting ahead through population studies

Rather than just chase after the actual infection events, broadly designed epidemiological population studies can give us a head start: Regular blood tests and tests on study subjects provide insights into past and current infections. Additional contact surveys can identify where the hotspots of infection are, for example in the workplace, in schools or in the private sphere, and which age groups are affected. A recently published major population-based study (MuSPAD) directed by Prof Gérard Krause and Berit Lange maps the infection scenario and unreported cases in several regions of Germany between July 2020 and August 2021. “The data are important to be able to apply measures in a meaningful and targeted way and be able to map the infection scenario over this period of time,” Lange says. “There is still room for improvement on how we conduct such studies more quickly and parallel to the ongoing infection events. By learning, for example, from the Office of National Statistics in the UK, which introduced and successfully implemented a periodical, national and very large population panel during the Corona pandemic.”

Vaccine research and information

Targeted and effective actions during a pandemic threat are key. Yet the best protection from infection and disease is still afforded by vaccinations. “We are very fortunate to have effective vaccines available after such a short time,” says Dirk Heinz.

“Without vaccines, we probably would be in an extremely difficult global emergency situation considering the highly contagious Delta variant, which currently predominates.”

“The close collaboration between government, science, administration and manufacturers worked well from very early in the pandemic and paved the way for the rapid vaccine development,” says Dr Peggy Riese, a scientist in the HZI Department of Vaccinology and Applied Microbiology. But the rapid approval especially of the novel mRNA vaccines also caused scepticism and uncertainty in the general public. “In terms of information policy and public relations, we truly need to become better for the next pandemic,” Riese says. “Since everything happened so quickly, many thought the vaccines were developed out of the blue - which is far from the truth. The mRNA platform has been in place for decades and has been used in cancer research for more than 20 years. It just has not achieved ground-breaking successes in the fight against malignant tumours yet. When the Corona pandemic hit, it was fairly obvious to check whether or not the mRNA technology might be suitable for development of a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2.”

Universal and tailor-made vaccines

Advantages of mRNA vaccines: They can be produced and adapted to new virus variants comparatively quickly. It also makes sense to develop universal vaccines that are effective against a wide range of dangerous variants of the pathogen. “This is where bioinformatics and so-called reverse vaccinology come into play as they will advance vaccine research by leaps and bounds,” says Peggy Riese. “With computer-based approaches, we can search for gene sequences that are present in many viral variants and thus identify a piece of mRNA for a vaccine that affords good protection against all known variants - and perhaps those yet to come as well.”

However, not every vaccination leads to the development of an efficient and long-lasting immune response. That is why we currently see a rise in the number of breakthrough infections. “We see especially in older people that the immune protection afforded by the Corona vaccines is not quite as good as in younger people and also that it decreases over time,” says Riese. Immune systems sometimes tick very differently. Riese’s research focusses on the underlying reasons and the processes that are involved: “Once we understand the mechanisms better, tailor-made vaccines could be developed that are adapted to the specific features of the immune system of certain groups of patients and protect these patients better.”

Vaccination through the nose

Vaccines are usually injected into a muscle. There is a problem, though: At the port of entry through which the pathogens normally enter our bodies - this would usually be the nasal mucosa in the case of respiratory infections - no local immune protection is evoked. “Conventional vaccinations do not confer immunity to the mucosa. This is one of the reasons why viruses can still be transmitted by vaccinated individuals,” explains Peggy Riese. In contrast, so-called nasal spray vaccinations act directly at the site of action. They stimulate the production of effective antibodies in the mucosa and thus prevent large amounts of virus from entering the body in the first place. In addition, a nasal spray vaccination is much more pleasant for the vaccinated person than an injection. Why isn’t it standard procedure then? “The nasal mucosa works like a barrier and makes every attempt to repel everything that comes from outside. Unfortunately, that also includes vaccines,” says Riese. “We are therefore searching for appropriate adjuvants that render a nasal spray vaccination both effective and safe. At the HZI, we are pursuing various approaches with immune adjuvants for this purpose that have already shown promising results in some preclinical studies.”

Effective antiviral drugs

Vaccinations can prevent most infections and severe courses of disease. But what if a person gets ill anyway? In this case the last straw are drugs, which do not only attenuate overshooting immune responses, but, ideally, also prevent further spread of the virus in the body. Great hope is being placed currently in two new effective anti-viral drugs that can even be administered orally, though general approval is still pending. “But the administration of antiviral drugs makes sense only early-on in the infection. If you miss the early stages, and this easily happens with Covid-19, which shows no symptoms early on, other drugs like immunosuppressive drugs have to step in to dampen the overshooting immune reaction,” explains Dirk Heinz. “The Corona pandemic has shown us very clearly: In addition to the extensive use of vaccines, effective therapeutic agents are also needed to control the pandemic.”

To be able to counter future pandemics with drugs as well, the HZI joined forces with the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) and recently developed a concept for the foundation of a National Alliance for Pandemic Therapeutics (NA-PATH). “We want NA-PATH to advance drug research aimed at dangerous and potentially dangerous pathogens - this includes, in particular, RNA viruses such as influenza viruses, Corona viruses or flaviviruses, which include Zika and dengue viruses - in a targeted manner,” says Heinz. “We need to be much better prepared for future pandemics due to novel pathogens, also with suitable medications. This is where infection research in Germany can and will make its contribution - by joining forces and pooling expertise.”

Autorin: Nicole Silbermann

![[Translate to English:] Berit Lange](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/6/csm_hzi_1911_berit-lange_epid_jab_005_8281d069d3.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Peggy Riese](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/7/csm_hzi_2012_peggy-riese_portrait_vac_vm_001_d6adbed464.jpg)