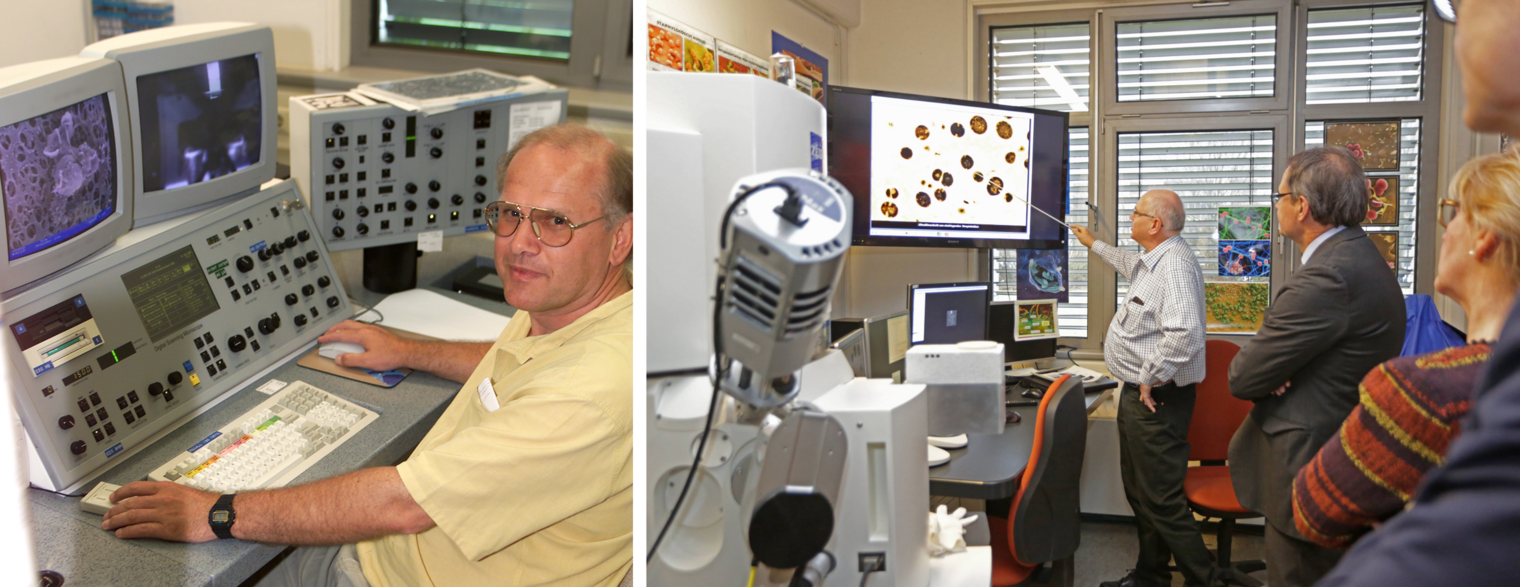

EM started in 1982 at the former Gesellschaft für Biotechnologische Forschung (GBF) and in 1989 moved into a new building, which presented a major challenge in itself: The floors of the new building were covered with vibrating screed, which is not suitable for microscopes, as they are highly sensitive to vibrations.

Paths into the unknown

In addition, the floors were covered in linoleum. Carpet would have made more sense here, as linoleum quickly ruptures when it comes into contact with nitrogen. But all these obstacles were overcome and the employees continue to do this today. Even the prospect of a slipped disc, which is an occupational hazard for microscope operators, cannot keep this true enthusiast from his work. “I have found my ecological niche here,” says Manfred Rohde. It is a passion that also requires talent. The human factor is still indispensable, because the eye sees far more than a comparison made by a computer programme, especially when that eye belongs to an experienced EM professional.

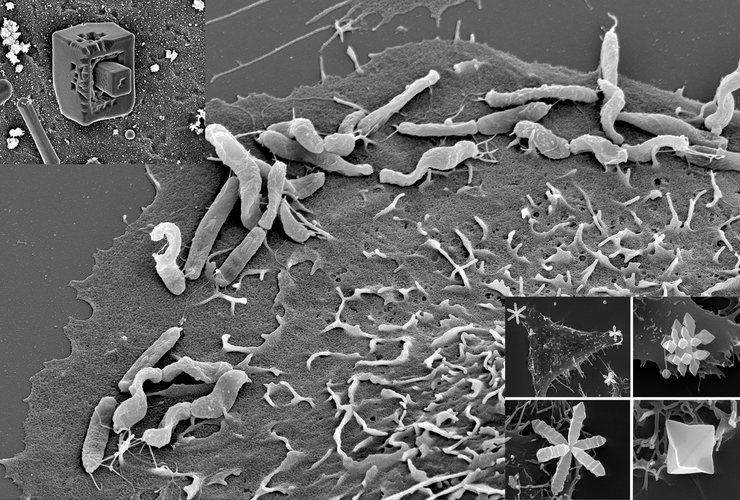

Good preparation is crucial for achieving good results, so manual work is required. The guiding principle here, pronounced with a wink, is “Crap in, crap out”. Sometimes even the most knowledgeable expert has to try different things to find the right method for a specific preparation. The goal is to preserve the structure, but collapsed membranes or burst cell walls are typical mishaps that occur on the path to achieving this. Rapid freezing in cryo-EM is especially essential for samples with a high water content, explains Rohde. Slowly reducing the temperature would lead to crystallisation and damage or even destroy the preparation. In addition, crystals obstruct the view of the most important thing, i.e. the organic material. Rapid freezing without crystallisation can be achieved through either lowering the temperature to -196 degrees Celsius or by using high-pressure freezing in liquid nitrogen at a pressure of 2000 bar. Cryo-EM, which was made possible as early as the end of the 1950s, has the advantage that the preparations remain absolutely pure, since no chemical additives are used – ultimately, it is just a matter of freezing.

A quote from the Spanish explorer Christopher Columbus can be applied to the motivation of the people who have found their vocation in microscopy: “When the old paths to the familiar are crowded and worn out, I will follow new paths into the unknown, overcome borders, expand my mind and return home with things that no one has ever seen before,” he said, according to legend. The unique insights that the microscopes, some of which are used at magnifications up to 200,000 times, offer are exactly that: images of the unknown and, in the moment of their discovery, reserved solely for the initiated. Over the years, the small departments at the GBF and later at the HZI typically consisted of just three scientists and a technical assistant, with two of the former TAs later even deciding to study biology out of enthusiasm for the subject.

“When the old paths to the familiar are crowded and worn out, I will follow new paths into the unknown, overcome borders, expand my mind and return home with things that no one has ever seen before"

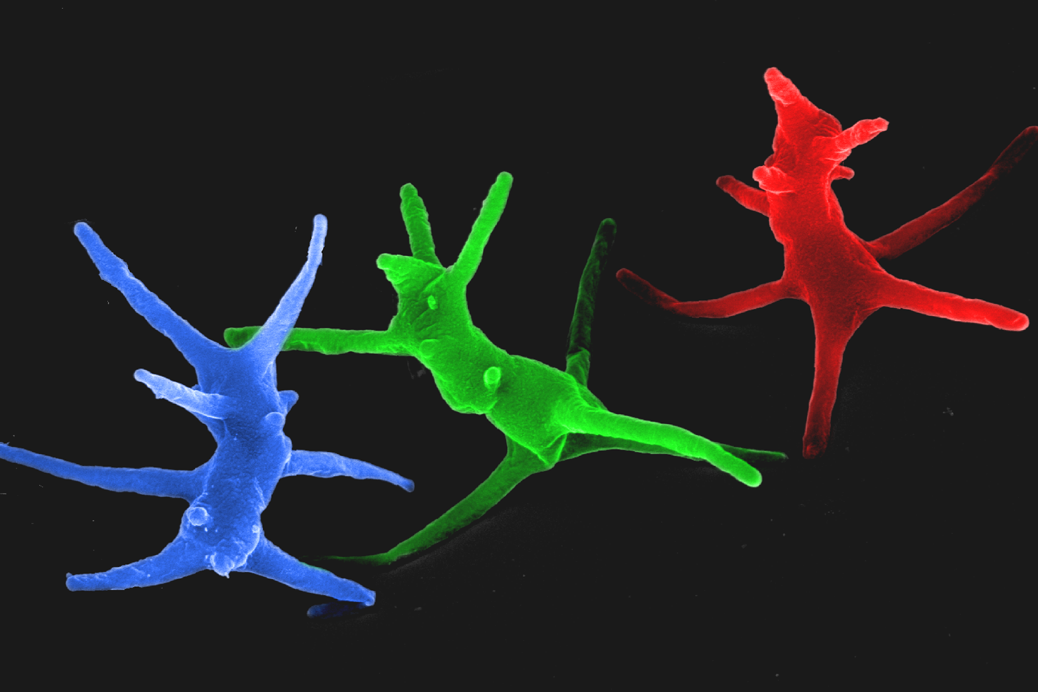

The images created by microscopy look as if they come from another world and evoke great fascination. The imaging possibilities have changed dramatically in recent decades, with the largest technical change that has had the most significant impact on everyday work being the invention of the “slow scan camera”. This means that images no longer have to be transferred to film plates as static single shots. The images are now digital and can be processed in any image-editing programme – and the pictures can be taken in daylight. The negatives that were previously used needed to be shot in the dark, and a darkroom was required. Two days a week had to be set aside for developing the images in the darkroom, meaning that this new technology also saves an enormous amount of time. “The digital scanning microscope has a screen, so it's similar to watching television,” says Manfred Rohde. But 20,000 old negatives are stored in the HZI archives and these are still usable for research purposes once they are magnified. One thing has not changed: black-and-white images are subsequently coloured. “This not only makes them more visually appealing, it also makes it easier to identify crucial details,” says Rohde.

In the equipment pool at the HZI, you will find cutting-edge technology being used alongside 26-year-old devices that are still performing well. Also still in use are the dimmable neon lights on the ceilings, which have been performing their duty since 1993 and were quite the sensation at the time. Manfred Rohde is grateful for both progress as well as stability. And that his first supervisor, Ken Timmis, gave him the freedom from day one to choose his assignments according to his own interests. This has led to many different collaborations, which have resulted in numerous publications in high-ranking journals. The microscopy unit at the HZI operates at the highest level of quality and discovers something new every day. Sometimes even with the naked eye. Christopher Columbus would have liked it.

Author: Christine Bentz

Published: December 2019