When the Wild Meets the Table

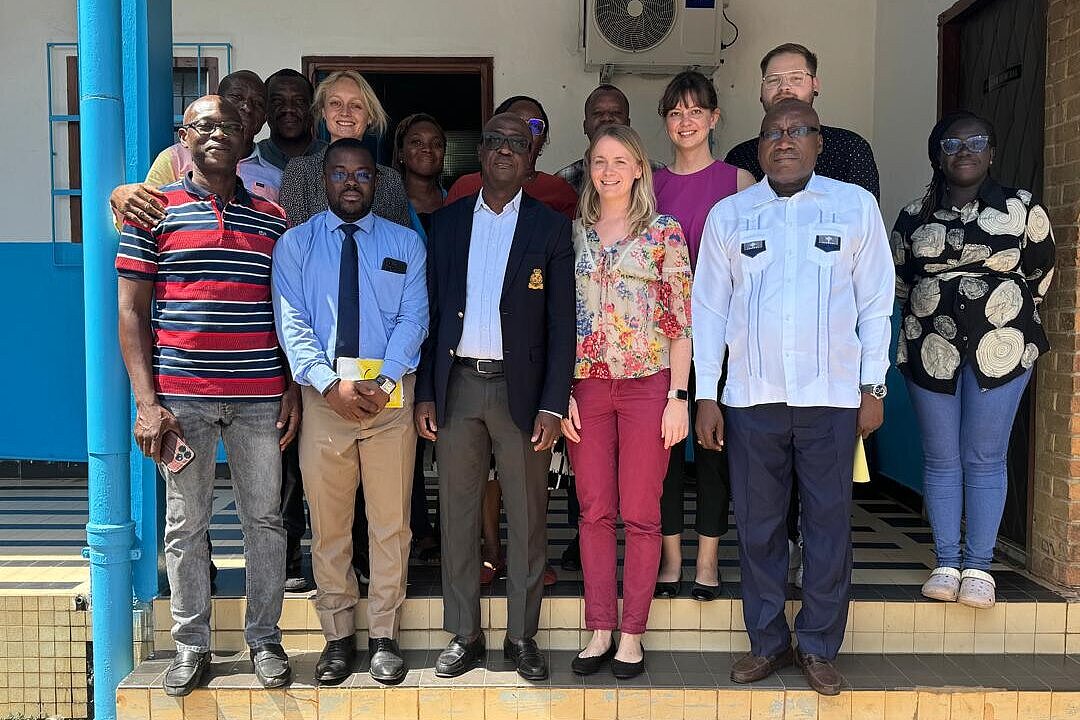

Two Ivorian PhD students in HIOH’s department “Ecology and Emergence of Zoonotic Diseases” participate in this project, which will run from 2023 to 2027 and is funded by the Volkswagen Foundation. Their mission is to characterize the marketed animal species and potential zoonotic agents present in bushmeat. During their PhD project, geneticist Nea Yves Noma (known as Noma), and veterinarian and epidemiologist Gbohounou Fabrice Gnali (Fabrice) are embedded in a large international and interdisciplinary network of partners headed by the Senckenberg Society for Nature Research, Frankfurt (Germany).

![[Translate to English:] Portrait](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/a/csm_Nea_Yves_Noma_6c232c58a1.jpg)

PhD student at Senckenberg Society for Nature Research, Frankfurt, visiting scientist at HIOH and assistant researcher in the genetics lab of Felix Houphouet Boigny University Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire.

![[Translate to English:] Portrait](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/4/csm_Fabrice_faacc8649b.jpg)

PhD student at Ecole Inter-Etat des Sciences et Médecine Vétérinaires de Dakar, Senegal, and currently visiting scientist at HIOH.

What is your research project about? What are you trying to find out?

Fabrice: Our research focuses primarily on the risk of zoonotic pathogen spillover through consumption of wildlife (bushmeat). Bushmeat can be a source of pathogens, which are transmitted from animals to humans and handling and eating it may thus facilitate the emergence of zoonotic diseases.

Noma: We are trying to find out which animals are sold as food in restaurants (so-called maquis) and which potential pathogens are associated to these animals. Our study sites are Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa.

Why is this important?

Noma: This is important because wildlife can be in contact with dangerous pathogens, particularly in tropical forests. For example, the causative agent of sylvatic anthrax, Mpox virus and Ebola virus have previously been found in our study area. We need to know which pathogens are present in our environment and associated to bushmeat to be able to raise awareness of the dangers that eating bushmeat can entail for human health and of the risks for decreasing biodiversity.

Fabrice: In a context where around 60% of human pathogens come from zoonotic diseases and some 75% of them are of wildlife origin, better characterizing the pathogen human interface will allow us to identify the entry points for interventions to change behavior with regard to bushmeat consumption. This may not only reduce the risk of the emergence of zoonoses, but also to reduce the pressure on wild fauna in our study area.

In which region(s) of the world do you conduct your research and which partners are involved?

Noma: Our research is carried out in the two neighboring countries Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia, from pristine and rural areas to peri-urban areas. While bushmeat hunting is officially banned in Côte d'Ivoire, it is not in Liberia. One of the objectives in this project will be to compare the two countries to see how different cultural values (to be assessed by an anthropologist in the project) as well as the legal framework influence bushmeat consumption and therefore potential pathogen exposure.

Fabrice: The interdisciplinary project brings together partners from veterinary medicine, ecology, anthropology and behavioral economics andis coordinated by the Senckenberg Museum of Natural History Görlitz, an institute of the Senckenberg Nature Research Society, Frankfurt (Germany). Other partners include Philipps University Marburg (Germany), École inter-États des Sciences et Médecine Vétérinaires de Dakar (EISMV, Senegal), the Université Jean Lorougnon Guede de Daloa (UJLOG, Côte d'Ivoire), and the Centre Suisse de Recherche Scientifique in Abidjan (CSRS, Côte d’Ivoire). The project is funded by the German Volkswagen Stiftung.

Which tools and technologies are essential for your work?

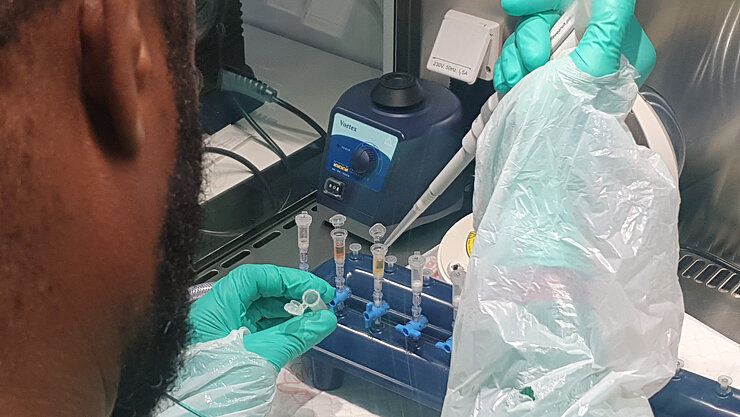

Fabrice: Our work requires a multidisciplinary approach and the use of various tools and technologies, including molecular diagnostic techniques such as next generation sequencing (NGS) and metabarcoding. In addition to these environmental methods, our partners in the consortium also use socioeconomic methods, such as surveys and interviews, to assess risk factors by asking people about their behaviors.

Noma: To collect samples during our field missions, we use swabs. That is, we swab the meat and surfaces in the restaurants (like table, kitchen tools etc.), and set up nets to catch flies that carry the DNA of both, the animals offered in the restaurants and the pathogens they may contain. We also sampled bushmeat directly if the restaurant owner allowed us. From these samples, we extract the DNA for subsequent characterization of marketed animal species and pathogen screening.

In which stage of your project are you right now? What did you find out?

Noma: We finished our first mission in Côte d’Ivoire in September 2024 and have recently extracted the nucleic acids from the swab samples taken in the restaurants. Currently, we are analyzing mammal sequences retrieved from the swabs to see which animals are marketed. Next, we will look for potential pathogens in the same samples. This first batch of analyses should be completed by autumn 2025.

Fabrice: Overall, during our first mission we took samples from 15 different animal species that were sold as bushmeat. These included mostly agouti and rat, but also, amongst others, viper, monkey, porcupine, gazelle, zibet cat, crocodile, duiker and deer. We are currently working on the analyses in the lab. The next step will be to prepare the fieldwork for our sampling in Liberia in October to December 2025. This will be the second and last of our missions for this project.

Are your investigations going as planned? Did you encounter any surprises or challenges?

Fabrice: Our work program is on schedule. There were a few technical difficulties linked to the initial adaptation of the nucleic acid extraction protocol to our swab samples and some of the administrative preparations for our mission in Liberia are challenging, but we will resolve these issues very soon. With regard to more fundamental challenges: Staying far away from my family for such a long time is difficult, especially for my children and my partner. I will be in Germany for a total of six months. But we manage, bearing in mind that this is the career I've chosen. Otherwise, my stay in Germany was and is very well organized and pleasant, thanks to my supervisor Dr. Lorenzo Lagostina, the HIOH Welcome team and the great HIOH family, including my compatriot and colleague Noma as well as other African colleagues. I hope to be able to return in the warmer months…

Noma: In science, any plan for an investigation may eventually run into difficulties – this is quite normal. For example, it can sometimes be challenging to convince restaurant owners to participate in our study and to allow us to sample their place and their meat. Particularly, since we do not pay them for their participation, so as not to encourage bushmeat trade and consumption. It’s a very sensitive topic. But we usually manage quite well. During my research stay in Germany, the only difficulties I have encountered were the language barrier (I’m a very beginner in German), and, of course, the long distance to my family and friends, with whom I keep in touch via social networks. But I must also emphasize that the spirit of integration which reigns at HIOH has allowed me to settle in better and to feel less far away from home – I sincerely thank the director of the institute, our supervisor Lorenzo and the whole wonderful team.

Why did you become a scientist?

Noma: I wanted to become a scientist because of my love of nature and my curiosity to understand this nature and our interaction with it.

Fabrice: Becoming a research scientist is a career choice that combines a passion for discovery, a contribution to the well-being of society, intellectual stimulation and opportunities for collaboration. I also wanted to contribute to the well-being of my country, and of the world in general, and to do something different from my basic training, even if my veterinary expertise is very helpful for the research work I do now.

What are your plans for after the end of this project?

Fabrice: Studying the potential pathogens in bushmeat capable of causing zoonoses will be a major discovery, but there are many other biotopes that are also capable of allowing zoonoses to emerge. At the end of this project, the aim will be to continue these investigations in other biotopes or gradients in order to identify the entry points and raise awareness and ultimately to promote healthier and more sustainable human behavior.

Noma: After my return to Côte d’Ivoire, I will use the experience and skills that I have gained during this project to teach at University. Moreover, I would like to be part of a scientific network for enhanced molecular diagnostics of animal samples together with the different partners from the BehaviorChange project in order to improve research capacities in my country – because we have a lot to do.

Interview: Dr Stephanie Markert