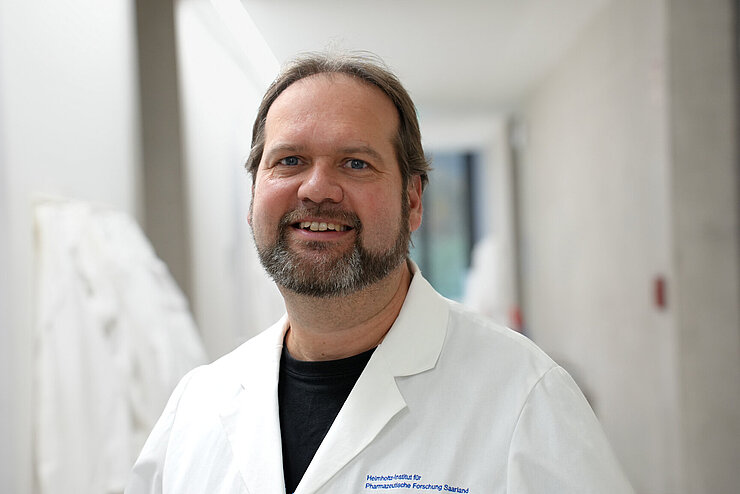

In this interview, three researchers from the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) and its sites in Saarbrücken and Greifswald report on how they are implementing aspects of this motto in their work. Dr. Daniel Krug, a scientist in the department “Microbial Natural Products” at the Helmholtz Institute for Pharmaceutical Research Saarland (HIPS), a site of the HZI in collaboration with Saarland University, is working with citizen scientists on the MICROBELIX project to find new antibiotic substances and to educate participants about AMR. Esteban Charria Girón, a doctoral researcher in the HZI department “Microbial Drugs”, is studying active substances from fungi that grow in the Colombian rainforest and advocates for the preservation of biodiversity. Prof. Katharina Schaufler, head of the department “Epidemiology and Ecology of Antimicrobial Resistance” at the Helmholtz Institute for One Health (HIOH), and her team are researching how resistant pathogens can spread. In the interview, she also gives advice which actions everyone can take to prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance. The HIOH is a site of the HZI in collaboration with the University of Greifswald, the University Medicine Greifswald and the Friedrich Loeffler Institute.

World Antimicrobial Resistance Awareness Week 2024: Educate. Advocate. Act now.

Dr Daniel Krug: “Educate.”

With MICROBELIX, anyone can become a researcher. Please explain the idea behind this citizen science project.

MICROBELIX is an invitation to everyone to immerse themselves with us in the biodiversity of microorganisms in the soil. The hope is to catch a glimpse of the otherwise invisible, which we can make visible through our research work. The very small things under our feet are always fascinating for many people.

In addition, there is of course the applied aspect that this biodiversity, which we discover together, is the input for a veritable research pipeline. At the end of this pipeline are new active ingredients. I think this interplay between the general idea of natural research and the idea of medical application is what makes this project so appealing.

In addition to the search for new drugs, MICROBELIX also aims to actively transfer knowledge to society. How does the MICROBELIX project educate participants on the importance of microorganisms in drug research, particularly with regard to antibiotics?

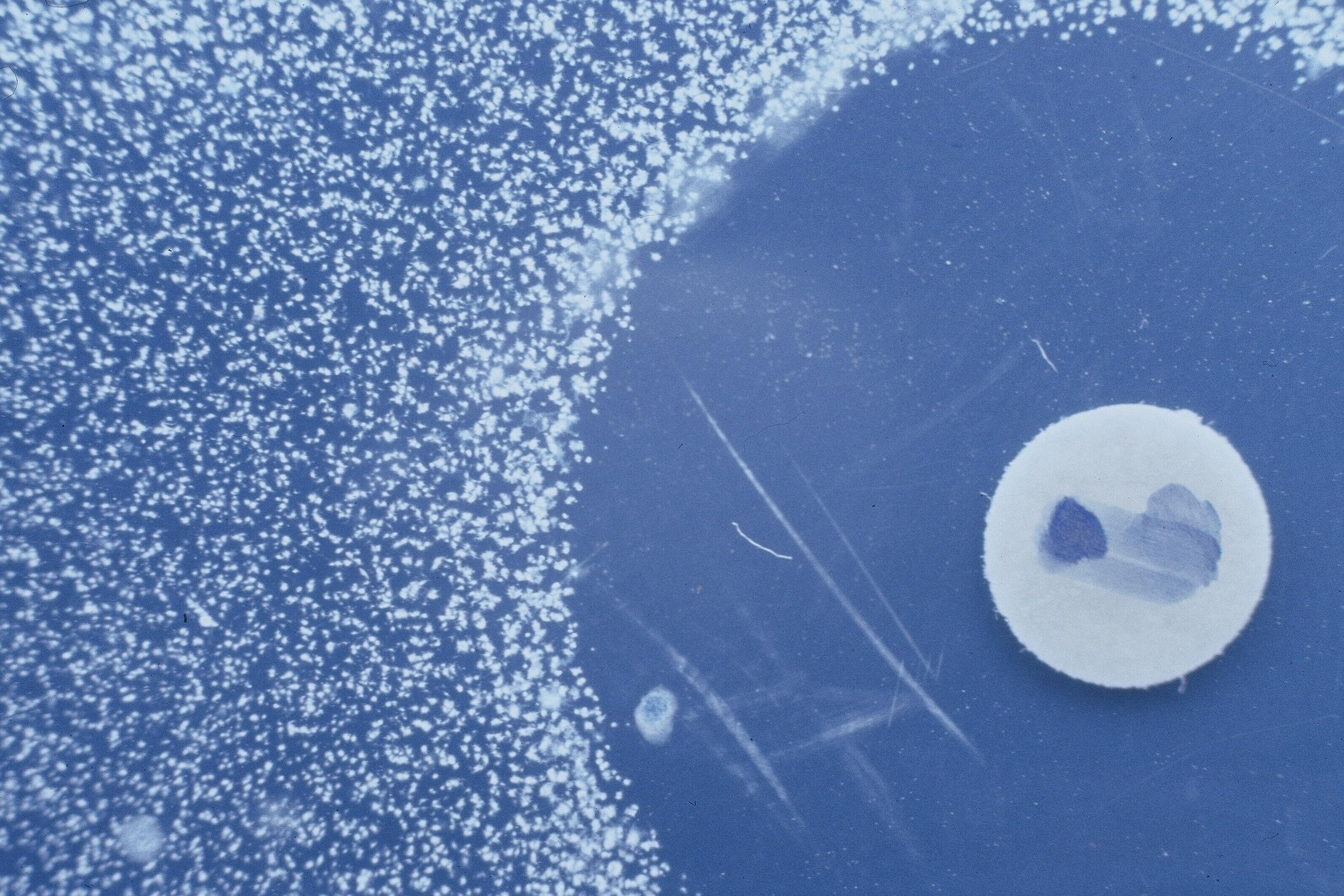

The first surprise that our citizen scientists usually have when we present our project is that antibiotics are not a human invention at all. Instead, their mode of action is regularly used in the soil, which is a highly competitive habitat for microorganisms. They engage in a kind of advanced neighborhood dispute with antibiotics. As slow-growing organisms, the myxobacteria that we are particularly researching here in Saarbrücken and in Braunschweig must be chemically all the more powerful in order to assert themselves in this habitat.

Why do you think it is particularly important for society to learn more about antibiotics and antibiotic resistance right now and how does MICROBELIX support this goal?

The coronavirus pandemic has pushed the issue of antimicrobial resistance into the background. We therefore think it is particularly important now to show that a kind of 'silent pandemic' is permanently underway. We run the risk of falling behind in terms of antibiotic resistance because the current practice of using antibiotics, including their use in animal fattening, has also led to the progressive development of resistance. We are currently in the position of having to come up with innovations and new active substances, because otherwise we will no longer have a reserve therapy for difficult-to-treat diseases.

Many people already have a gratifyingly enlightened level of knowledge about this and are therefore personally very enthusiastic about MICROBELIX. Even if you don't know whether your own soil samples will be successful, you can still make an active contribution.

Esteban Charria Girón: “Advocate.”

At first glance, biodiversity and drug research are two topics that are not directly related. As a researcher, how are you committed to preserving biodiversity and how does this relate to your research into the development of new antimicrobial agents?

Though these two topics may seem unrelated at first, biodiversity and drug research are deeply interconnected. Microbial biodiversity has been historically an essential resource for discovering new antimicrobial agents. Part of my research focuses on exploring microbial species, particularly fungi, which have evolved unique biochemical mechanisms over millennia to survive. By studying these species and their evolutionary traits, we aim to translate microbial diversity into chemical diversity—unlocking potential new antibiotics. However, this is only possible if biodiversity is preserved, stressing the urgency of conservation efforts worldwide.

As part of World Antimicrobial Resistance Awareness Week, how does the protection of biodiversity, particularly fungi, contribute to solving the antibiotic resistance crisis?

In my work in the department “Microbial Drugs” (MWIS), I focus on fungi, as certain taxa are prolific sources of antimicrobial molecules. Despite the immense diversity of fungi, currently we have only identified a small fraction of species worldwide. This situation is even more pronounced in biodiversity hotspots, such as tropical countries like Colombia, where I’m from. Although these regions hold tremendous potential, they often lack coordinated efforts and infrastructure to fully explore their biodiversity. Through global research expeditions, we collect and characterize fungal species, aiming to unlock new antibiotics. This biodiversity-first approach offers fresh strategies to tackle antibiotic resistance, with the aim of providing solutions beyond the reach of current drugs.

What motivates you personally to work for biodiversity both in research and publicly, and why is this so important for antibiotics research?

Coming from Colombia, where natural wealth contrasts with challenges like severe biodiversity loss, I feel a responsibility to take action. As researchers, we often live in a bubble, focused on lab work or analyses, forgetting the world beyond our data. However, I have the privilege to work alongside scientists whose responsibilities extend beyond publications, such as my supervisor Marc Stadler. As a member of BioGeCo, a Colombian-German network for science and innovation, and the Colombian Cross-Sector Board for Science Diplomacy (MIDICI), I have the opportunity to advocate for biodiversity, as I did recently at COP16 in Cali. I communicate the immense value it holds for discoveries, such as in the search of antibiotics, to policymakers and stakeholders. My hope is that, together, we can drive change — now.

Prof Katharina Schaufler: “Act now.”

How do your research approaches contribute to understanding and combating the emergence and spread of multi-resistant pathogens?

Our research analyzes factors that promote the success of specific multidrug-resistant pathogens. We are investigating which genes contribute to the antibiotic resistance, virulence and fitness of these pathogens and how they spread in different environments. With the help of genome analyses and laboratory experiments, such as biofilm formation and mortality tests in wax moth larvae, we are gaining deeper insights into the mechanisms that promote the spread and resistance of these pathogens. As part of the DISPATch_MRGN project, we are also researching alternative therapeutic strategies by identifying new points of attack in multi-resistant pathogens and testing natural substances that have a targeted effect without damaging the healthy microflora.

The World Antimicrobial Resistance Awareness Week raises awareness worldwide about the responsible use of antibiotics. What can we do in our everyday live to limit the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance?

The most important step is to understand that everyone can contribute to preventing the spread of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics should only be taken as prescribed by a doctor and the dosage and times of administration should be strictly adhered to. In addition, antibiotics that are not needed should never be disposed of down the drain. Regular hand washing, hygiene and adequate vaccination also help to prevent infections and reduce the use of antibiotics. Careful kitchen hygiene, especially when handling raw meat, is also an important contribution to reducing infections.

How does the One Health approach of your research support the protection of humans, animals and the environment from antibiotic resistance?

The One Health approach integrates the health aspects of humans, animals and the environment, as antibiotic resistance is often transmitted at the interfaces between these areas. As part of the BALTIC-AMR project, for example, we are investigating the spread of multi-resistant bacteria and antibiotic residues in the Baltic Sea and their potential impact on humans and animals. A recent study we published in npj Clean Water has shown how resistant pathogens can circulate in water bodies and thus increase the risk of resistance spreading. Such research helps us to better understand the pathways and reservoirs of resistance and to develop targeted containment measures to sustainably protect human, animal and environmental health.

![Dr Charlotte Schwenner [Translate to English:] Charlotte Schwenner](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/9/csm_Charlotte_Schwenner_7952cfe0a7.webp)